Morning Remembrance

As Big Gav notes, we have lost a keen observer on energy issues, the Nobel-prize winning chemist Richard E. Smalley from Rice University. I had the honor of seeing Smalley speak as a conference key-note several years ago, and he stirred me to think about our energy predicament in a way that I hadn't since my teenage years in the late 70's. The fact that he recently had become one of the most articulate scientific spokesman for energy and water issues also boded well for our future. He may not have solved it with his proposals for a nanotechnology-based energy grid, but he sure could smell out the overly ripe ideas, from abiotic oil to tidal power.

If Smalley had a morbid sense of humor, he would probably appreciate this audio remembrance from Air America Radio's Morning Sedition [WMA]1. When I heard Smalley's name suddenly mentioned in this comedy bit, it shocked me quite a bit -- heightened by the fact that environmentalist Jim "Mort Mortenson" Earl doesn't joke about the identity of the person, only about the absurd process of dying. But then I thought about my own experiences in the materials science field. Not having a clue that Smalley had survived with a cancer diagnosis the last few years, it made sense in my probabilistic mind that if Smalley had to expire, then a mutagenic ending would seem most fitting. You see, as most everyone in the chemistry profession understands as tribal knowledge, chemists do not live as long as other scientists. All the bad chemicals they (ingest, sniff, absorb, spill) tend to accumulate over time. And if you happen to work in the semiconductor field, you have to deal with HF burns (a fellow student of mine had a nasty one the length of his arm) and the accidental inhaling of same. I had heard apocryphal horror stories such as the case of all the techs working at a state-of-the-art facility dying over the span of a few years. And then you had all the benzene and other solvents to deal with in the pre-EPA days. (Don't you know that since getting away from chemistry, I now happen to spend a lot of time sitting on top of a super-fund site.) Without knowing the exact cancer that befell Smalley, I have a feeling that he mixed a lot of bad stuff as a grad student and post-doc. It finally caught up to him.

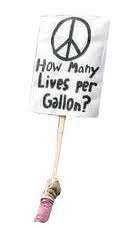

Which gets us to Smalley's ballsy attitude. I like to think I can go after peak-oil optimists like Michael Lynch with just a dose of the courage that Smalley has mustered up the last few years. It helps to have a BS detector highly tuned thanks to witnessing the way top scientists have operated over the years.

Specifically, I called Lynch on his assertion of having an oil depletion model published in a "refereed" journal.

9. A simple supply model (and its shortcomings)Which clearly shows that he has no model. And then I learn the fact that his journal article came from a "boutique" publication that had a lifetime of a few years. Sure enough, it seemed to stop publishing in the year his article came out. Somebody has to stop Lynch from preaching this crap. But who will do it?

In theory, a bottom-up, microeconomic supply model can be developed with clear-cut dependent and explanatory variables: Price (or revenue) leads to exploration expenditures and thus drilling, which cause discoveries, discoveries are developed into capacity which is produced. Various factors such as cost and depletion modify the outcomes, but in theory, all of these would be amenable to simple econometric modeling (see Table 1). However, such a model has proved impossible to construct for a variety of reasons. -- "The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance", 2002

While in graduate school, I worked with a post-doc who got his Physics PhD from Rice U. Although he didn't work with Smalley directly, I remember him telling me how arrogantly Smalley acted as a research colleague and intimidating presence. In retrospect, I think this attitude had more to do with taking the research by the balls if you want to make your point, or at least make any progress.

So, why am I personally working on this oil depletion topic when I happen to have an advanced degree in a completely related field?

Better still -- Why did Professor Smalley give lectures in a field outside his area of expertise, with keynote addresses, hearings before congress, and his taking on a bunch of wild-eyed energy optimists, all the while trying to beat the cancer that had slowly eaten away at him the last few years? Why did he try to make us all aware of our dire energy predicament even though he could have rested on his Nobel prize laurels? Why did he urge everyone he ran across to help get young people interested in math and science, even though he remained a royal pain to deal with one-on-one on a technical level?

Because he probably gave a damn, that's why.

If that sounds pretentious, too bad. At least you know why some people don't care to suffer fools. That dude took no prisoners. Kurzweil and Drexler, that includes you as well. Sometime soon a progeny of Smalley, perhaps as Mortenson coined it, a nano-condensed Dick Tiny, will soon come after your reputation, because you guys have nothing else to offer.

1Morning Sedition is going through a possible death scene on its own, with angsty host Marc Maron apparently on his way out. Dang, double whammy.

2 Comments:

I met Smalley only last spring, interviewing him for a book distantly related to energy issues. We hit it off, and were planning a collaborative article expanding on the "Terawatt Challenge" presentation until he became too ill to continue.

The best answer I can come up with for your "Why did he..?" can be summed up as: do the math. He had done so, with no ideological preconceptions for or against any energy source -- fossil or renewable, big or small, local or central, baseline or peak-load. And he simply couldn't add the numbers up to meet even conservative, growth-as-usual projections for global needs by 2050... let alone projections that would bring a billion or two more people out of poverty.

He was idealistic enough to want the latter very much. But I think even deeper than that was a cold-eyed mathematical and scientific conviction: that if we don't discover and develop qualitatively new sources as well as ramping up the existing ones fast, there aren't any pretty outcomes by 2050... and very few that are even tolerable.

Interesting, I told someone recently to "Show me the Math!"

Post a Comment

<< Home